3-D printing is a sizzling topic that is rapidly gaining notoriety in the food realm. Many believe that it will transform the future of food and the way we consume and prepare it.

It can assist in the creation of complex sweets for professional patisseries and chocolatiers, it can inspire creativity in home cooks and give them unlimited control over a meal’s shape, consistency, flavour and colour, it can be useful for long-distance space travel and eventually it may help to combat world hunger.

Others believe that printed meals from cartridges of powders and oils high in fat and salt, highlights the failings of our current food system. If we continue to produce processed technicolour foods, how will we learn to feed ourselves healthily and sustainably?

The debate is heated. Tech-loving optimists vs. nature-loving realists? It’s complex, and the conversations continue to swelter.

Jeffrey Lipton, co-founder and CTO of Seraph Robotics is an expert in the field, and graced the headquarters of the Food Innovation Program (FIP) in Reggio Emilia for one week to demystify digital food.

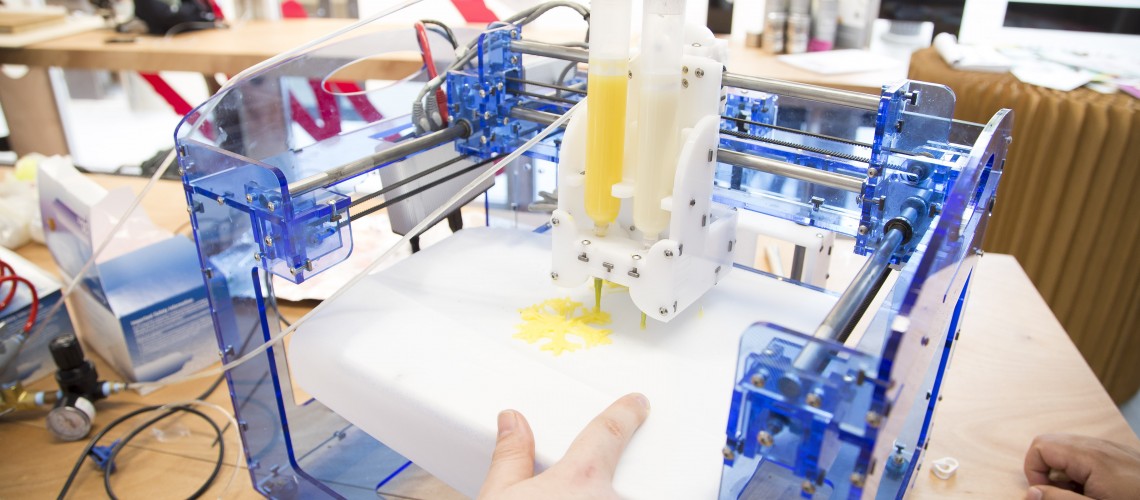

In layman terms, a 3-D printer is about the size of a microwave and looks like a hot-glue gun attached to a robotic arm. However instead of squeezing out glue, the cartridges ooze out plastic, metal, biological tissue or food…soft or liquid materials (pastes and fluids) work best (think hummus and peanut butter).

Using special CAD software (a computer aided design model), you can design any object on your computer and then load your digital blueprint into the 3-D printer. The printer nozzle will map out your object, by releasing the soft materials layer by layer into the desired shape.

Our own home-grown 3-D printing expert, building engineer and architecture student, Antonio Gagliardi, has always been interested in the digital fabrication field. “Four years ago I discovered the awesome RepRap project, so I decided to follow the project and build a 3-D printer by myself. It took four months and during the process I learned all about how a 3-D printer works,” he says.

Having Lipton at FIP was an amazing opportunity for all students to dive head first into the world of digital food. Gagliardi explains that the week was jam packed with activities and culminated in mounting and setting up a 3-D food printer. “There were four lectures held on 3-D printing, which looked at the different technologies in additive manufacturing, the approaches to 3-D printed food, peculiarities, and exploring the different fields involved in the process. We were also provided with an overview on the future of 3-D food printing, by looking at some case studies. We then looked at 3-D modeling by exploring different approaches of CAD as well as some “on the edge” methods, using genetic algorithms, computational design based on the complexity theory and stochastic patterns. We brainstormed ideas in teams to develop product solutions with 3-D food printing and had a short introduction to Python programming language. After, we tested our ideas by preparing the materials using molecular cooking techniques and printing.”

Having already worked for four years on his own 3-D projects, Gagliardi is no stranger to the field. Yet he notes that “it was really interesting to see how our teacher developed the fab@home 3-D printer, a user-friendly printer with easy-to-use software, both addressed to food and biology research. I liked the experiment he did with his team by setting up a web page where the user is involved in an endless shape generation process using a genetic approach”

During the workshop Gagliardi explored a different approach, and essentially “hacked” the standard method of the 3-D printer. “Instead of producing the model layer by layer I deposited the filament from a certain distance to have a random part in my design. The path the 3-D printer followed was a pattern that I generated with an algorithm inspired by the spirograph movement. At the end of the print you obtain a nest of wires”. The subsequent idea was to use this ‘nest’ to decorate the final team design – a Bloody Mary cocktail.

Whilst 3-D printing is incredibly cool and otherworldly, it is also surprisingly difficult to master. Gagliardi believes that at the moment the 3-D printer can’t be used as a household tool “because the technology currently used to print food is the FDM (filament deposition method), which is technically old. It was patented in 1984 by Stratasys and intended to work with plastic.” Printing food in this way is limited as the deposition of layers generates an undesirable texture, the process is incredibly slow (so the time to receive your meal would be too high) and there are many limitations with the materials that you can use.

“Digital cooking can be the future of food if we look under the iceberg’s tip, which is the way 3-D printing is heading. There is a huge system of automation and fabrication that is becoming affordable for anybody to experiment with. This will be the future of food production; open source technologies and combining different knowledge to (re)invent,” says Gagliardi

Incredibly passionate about this field Gagliardi has set-up and calibrated a fab@home and is currently working on a concept “to use 3-D food printing to help children with dysphagia (swallowing problems) or autism to eat better on a psychological and nutritional level”.

© 2015 Food Innovation Master Degree | © 2014 FUTURE FOOD INSTITUTE